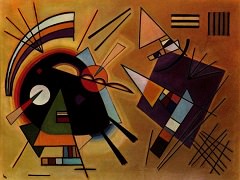

Mit und Gegen, 1929 by Wassily Kandinsky

Kandinsky's analyses on forms and colours result not from simple, arbitrary idea-associations but from the painter's inner experience. He spent years creating abstract, sensorially rich paintings, working with form and colour, tirelessly observing his own paintings and those of other artists, noting their effects on his sense of colour. This subjective experience is something that anyone can do - not scientific, objective observations but inner, subjective ones, what French philosopher Michel Henry calls "absolute subjectivity" or the "absolute phenomenological life".

Published in 1912, Kandinsky's text, Du Spirituel dans l'art, defines three types of painting; impressions, improvisations and compositions. While impressions are based on an external reality that serves as a starting point, improvisations and compositions depict images emergent from the unconscious, though composition is developed from a more formal point of view. Kandinsky compares the spiritual life of humanity to a pyramid - the artist has a mission to lead others to the pinnacle with his work. The point of the pyramid is those few, great artists. It is a spiritual pyramid, advancing and ascending slowly even if it sometimes appears immobile. During decadent periods, the soul sinks to the bottom of the pyramid; humanity searches only for external success, ignoring spiritual forces.

For Kandinsky, the principle of art and the foundation of forms and the harmony of colours is "Inner necessity". He defines it as the principle of efficient contact of the form with the human soul. Every form is the delimitation of a surface by another one; it possesses an inner content, the effect it produces on one who looks at it attentively. This inner necessity is the right of the artist to unlimited freedom, but this freedom becomes licence if it is not founded on such a necessity. Art is born from the inner necessity of the artist in an enigmatic, mystical way through which it acquires an autonomous life; it becomes an independent subject, animated by a spiritual breath.

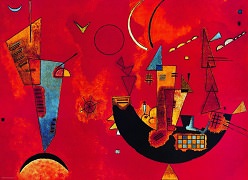

Red is a warm colour, lively and agitated; it is forceful, a movement in itself. Mixed with black it becomes brown, a hard colour. Mixed with yellow, it gains in warmth and becomes orange, which imparts an irradiating movement on its surroundings. When red is mixed with blue it moves away from man to become purple, which is a cool red. Red and green form the third great contrast, and orange and purple the fourth.

Mit und Gegen, 1929 is the best interpretation of Kandinsky's theory.